A lengthy article taken from the Scotsman of 22nd November with loads of background on the album, etc.

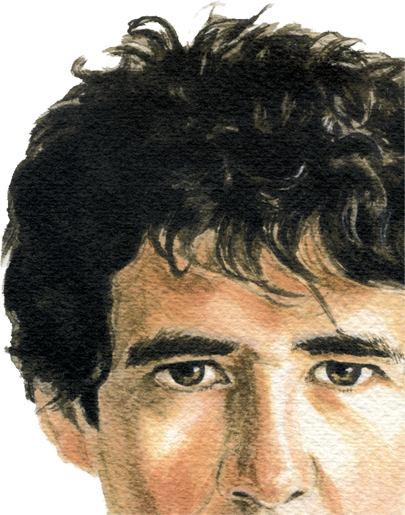

The first time he saw Beatles films on TV, Stevie Jackson wanted to be a pop musician – but he never craved the spotlight. He guitarist tells Fiona Shepherd what’s changed

WHEN Stevie Jackson was a teenager, someone told him that names ending in “son” were of Scandinavian origin. Jackson decided then that his debut solo album would be called Jackson Viking.

About ten years later, he was gigging in Europe and short on cash for the next round of drinks so he nipped outside, busked a version of The Rolling Stones’ Satisfaction and made the requisite beer money. One of his bandmates of the time coined the phrase I Can’t Get No Stevie Jackson, and Jackson slipped a new album title into his back pocket.

Several moons later, the title now has an album to go with it and the man best known as Belle & Sebastian’s guitarist, who describes himself as “one of nature’s sidemen,” is out on tour fronting his own band.

Jackson has made informal solo appearances many times over the years – he was first approached by Belle & Sebastian frontman Stuart Murdoch to join his new band while playing an open mic session at The Halt Bar in Glasgow – but as he notes, “there’s a big difference between doing the odd gig and actually having a record out, and your name being on the ticket.”

(I Can’t Get No) Stevie Jackson – also the name on the ticket – came together in increments over the last five years but has been brewing for some time. With the exception of band leader Murdoch, Jackson has contributed more songs to the Belle & Sebastian catalogue than anyone else – generally upbeat, witty and hooky tracks with a retro spin and a dusting of pop culture references. His own album is infused with a similar panache but it’s an eclectic collection.

“I quite enjoy modern R&B records and there’s one song called Just, Just So To The Point that was self-consciously trying to do something in that style,” he says. “With some of the other tunes, it’s more about getting the players in a room and seeing what happens. I like the spontaneity, I like to just get people together and hit ‘record’ so hopefully it has got a liveliness about it. When I’m making records, I like it to be quite fast. Don’t let the band learn it too well.”

Taking the informal, collaborative approach, he managed one day in the studio with two of his favourite musicians, Pastels drummer Katrina Mitchell and composer/ pianist Bill Wells, but came unstuck when he tried to repeat the trick with the same players. “Could I get them together in the same room again? No. It was just too hard. I should have booked people three months in advance, instead of saying ‘let’s get together one day’. That didn’t work.”

In contrast, Jackson worked with artist Nicola Atkinson on a couple of formal commissions, working to a deadline. One of the album’s most reflective numbers, Bird’s Eye View, came from this collaboration, inspired by the Abbey View housing project in Dunfermline, where Atkinson is artist-in-residence.

But most of the songs came out of a weekly musical kickabout with friends, singer/guitarist Roy Moller (the inspiration for the Jackson-penned B&S song Roy Walker) and drummer Gary Thom, collectively known as The Company. For the first time in years, Jackson was playing music for the sheer enjoyment of it. “I felt like a teenager again,” he says.

Jackson was given his first guitar in his early teens but he had been working up to this momentous occasion for some time. “I knew when I was seven years old that I’d end up doing this,” he says. “There was a season of Beatles films on telly and from that point on, that was it. It was inevitable that I would get a guitar. And before I had a guitar I had a badminton racket and I would play that.”

Jackson would provide the backing for the singsongs at family parties (on guitar, not badminton racket). At the same time, he was devouring the pop music of the day. His first album was The Police’s Regatta de Blanc and he also cites Madness, Abba, OMD, Depeche Mode and ABC – all great melodic pop bands. We spend a few minutes gushing over the brilliance of the Dave Edmunds’ hit Girls Talk, written by Elvis Costello (of whom Jackson can do a mean impersonation).

In his mid-teens he got together with a friend from school and they spent several years playing bar gigs and anticipating pop stardom. One of the sunniest songs on the album, Richie Now, celebrates this time from a nostalgic perspective.

“When you’re 14, 15 and you get together and start making a noise, it is the world opening up,” says Jackson. “You have that indestructible feeling when you’re young. But your ambitions when you are 13 are different when you’re 25. By that time, your ambition isn’t to be a star anymore, it’s to make a living doing music. Me and Rick stopped playing together when we were 22 because I think in our heads we thought, ‘we’ve not made it and we’re 22, so we should grow up and get a job’.”

Jackson came out of self-imposed musical retirement a couple of years later and joined a local band called The Moondials after hearing their singer busking on Glasgow’s Buchanan Street. “I’d been to a job interview which was unsuccessful, but bizarrely – and this shows you how serious I was about the job interview – I had a harmonica in my pocket, so I started playing along with him.” Again, the natural sideman thing.

Despite remembering this time fondly, by the time the band split Jackson was considering retirement again. When Stuart Murdoch showed up looking for a guitarist, he was a reluctant recruit. “But we made the record [Belle & Sebastian’s debut album Tigermilk] and it came out so good that we never talked about it again,” he recalls. “The ball was rolling just at the point when I really wanted to retire. I mean, 22 was old but 26 was just getting a bit embarrassing. Back then, I didn’t even want to be photographed because I felt too old.”

For the first couple of whirlwind years, everything was rosy in the Belles camp but this was followed by what Jackson describes as “five years of dysfunction” which he attributes to sudden, unexpected success, the big age gap between band members and those differing ambitions he has talked about. “But I don’t like putting a negative vibe on it because obviously, we produced a lot of good work.”

After the storming came the norming and performing, and the group has been a steady unit for the past ten years, secure enough for members to go off and do their own projects, such as Murdoch’s God Help The Girl.

“I’ve learned from Belle & Sebastian, Stuart Murdoch in particular,” says Jackson.

“He told me an important lesson. It’s not about blasting people in the face, it’s about drawing people in. And he is a genius at that. He can just stand there with his guitar and his words, and everyone goes quiet and starts listening.

“That’s a skill. So that’s the next challenge, taking it out.”